by Rev. Fr. C Byrne, OMI, about May 1961

As told by Mr Ned (Edward) Hughes

I received word in 1909 that I was to come to South Africa. I had been working in the factory there, then I left the factory in Arklow in Ireland and was away for eight or nine months. The manager’s brother was sent to find me to know if I would come out to South Africa, so I went to see him, the manager, and I agreed, and the conditions were – I was married at the time with one child – a free passage out for myself, my wife and child, £5 travelling expenses to Umbogintwini. £5 was quite a lot at that time.

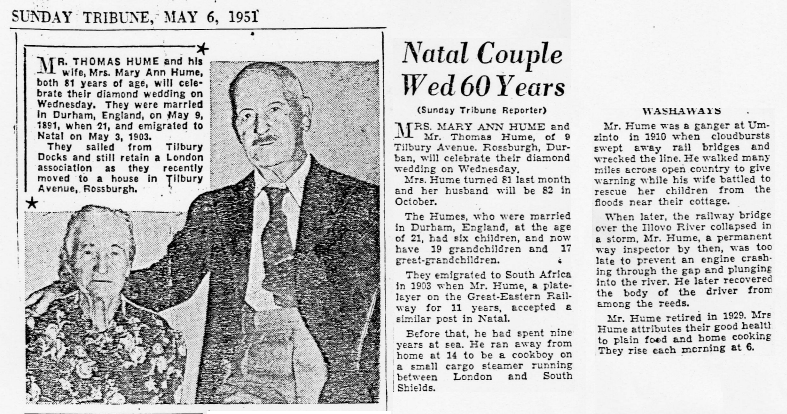

My wife’s name was Kathleen Denehy, she belonged to Corkril. I belong to a village about three miles outside Arklow, a village called Culgrany, between Arklow and Gory. My first child is called Jack – John, he alive, living in Jubilee Court, Clarence Road in Durban. He was about six months old when I come out here. We sailed on the “Norman”, Union Castle Line from Southampton. We arrived out here on the 10 January 1910. I didn’t come out with the first contingent, there was another lot come out before. In the first contingent was John Joe Kelly, Pat O’Connell, Peter Dempsy, Simon Kenny, Jack O’Neill.

At first there was no Umbogintwini, we had to first of all to take a house in Isipingo, I, the wife and child lived in the house at the back of the hotel, and then we moved from there down to Amanzimtoti, and we took a house which was very, very dilapidated, in fact it was an old house full of rats, the furniture was terrible, real awful, in fact one night we were sitting in the house in the evening, when I come home from work, and the piano started playing, and there was nobody near it, and we thought the place was haunted. It made me think, we couldn’t understand that, didn’t give it a thought it was rats. I went over and lifted the top of the piano, and if one rat jumped out of it there was hundreds, they went up and down the piano and walls. It was an old dilapidated shack.

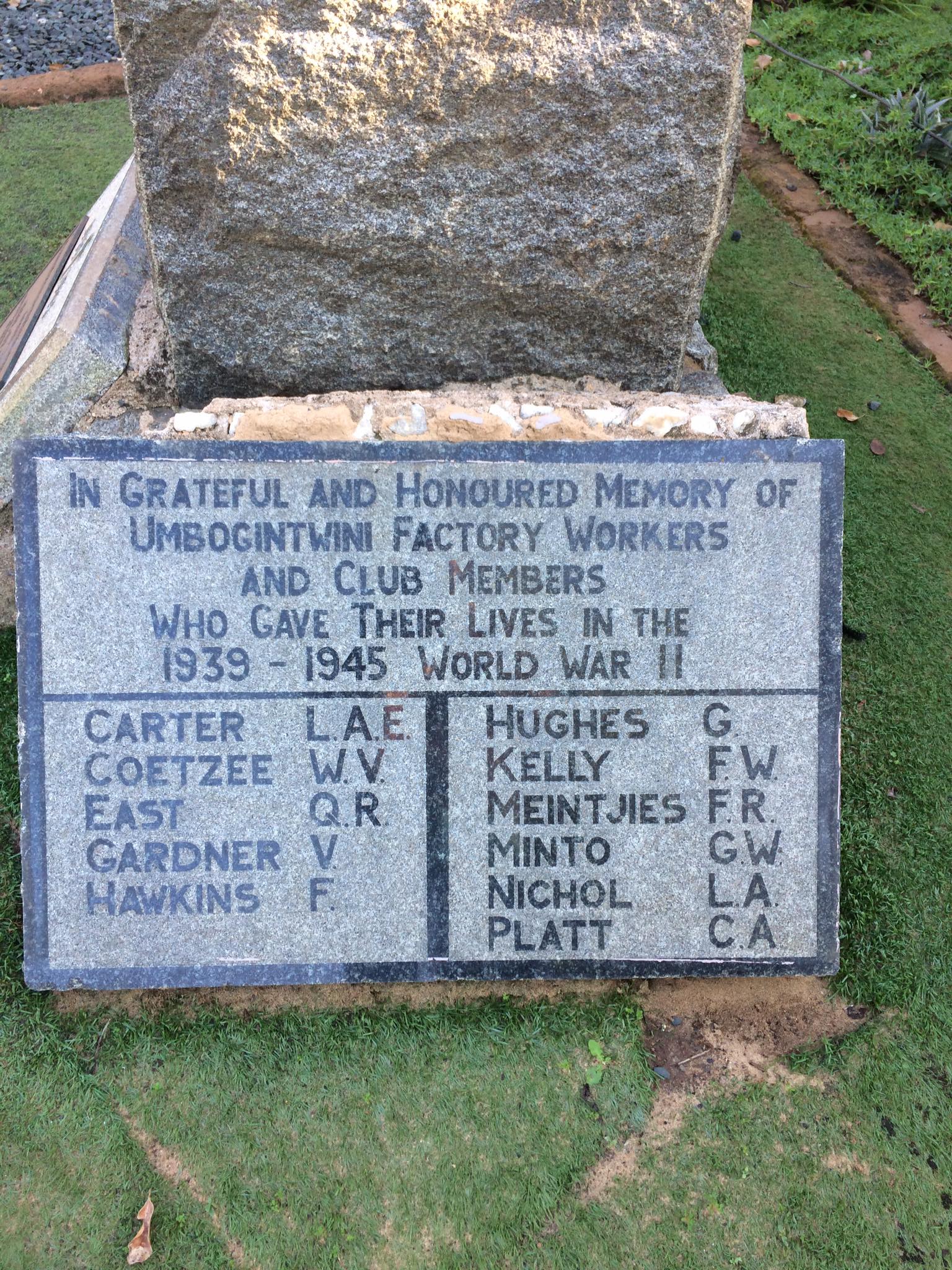

Oh, the poor wife, battling along with the one child said, “Why did you bring us to this country?” I said, “I don’t know, I said, I don’t know why I come myself, but we’re here now, we can’t go back, so then we’re going to remain here, I said it’s too far to swim, too far to walk, and I’ve no money, and I’ve signed a contract for two years, so it’s impossible to get back.” I never went back, not until I finished in 1947, my wife never went back. The children were Jack, the eldest, Gerald who was killed at Mersa Matru in the Second World War; he was in the 2nd Anti Tank Regiment from Durban. There’s Paula in Pinetown, Kathleen and Tessie, a Sister of Nazareth now, and there’s a boy Edward died.

I come out here to work on explosives. After the first explosion here, there was a young fellow killed, Kelly, so they cabled home for six more men to come out here, but they didn’t state that there had been an explosion. I had a two year contract, £3 a week, return passage at the end of two years if I wanted to go back. By then I was married and settled down, with the family increasing and it was no good going back. I had a bit of bad luck too, the one child, my namesake, he got poisoned drinking paraffin oil. He was about 15 months old, and I come off a double shift working at the factory and he was in the room playing with me, the mother was in the kitchen making a cake or something, so I called the mother to take him away. At that time there was no electric light in the houses. The house was in Umbogintwini now, they had just started building houses, one of the first houses; so we had a tin of paraffin oil with a pump in it, and an old milk tin underneath it to catch the dregs and apparently this kid got in and was drinking from the tin and it went down his neck and he suffocated. Oh, it was terrible; there was no doctor at that time, very primitive.

This would be about 1912 I should say, about two years in Amanzimtoti.

During the First World War I tried to join up, but on account of munition-making, they were making gun-cotton down here and nobody making munitions were allowed to join up, you’d be sent back, in fact, the manager told us if you went to the recruiting offices, you’d be sent back.

The voyage coming out was beyond the normal shipsy roll, bakin’ and twisting, but on the whole it was a fairly good passage. I think it took about 21 days. Of course I didn’t see much of my wife, she was a very bad sailor and then having Jack at six months old coming out too.

The first of the Irish colony in Umbogintwini was like a real little Ireland. One coming after the other, and the houses got built, we got settled in the village and we had our own entertainments in the houses, little parties, and invited to your house this week and my house next week and something like that and it wasn’t bad on the whole. On Christmas Day we got together talking at the old club, which was in a house, and stood talking like we always do.

The first Mass for the Irish was said down at Amanzimtoti, at a private house, Mr & Mrs Knott, a Dublin man, his wife was from Arklow, and the Priest was Father Tual. We used to have Mass in our house and then someone else’s, change about.

As told by Mrs Margaret O’Brien

I came to South Africa from Arklow in 1912 on the “Dover Castle”. My husband’s name was Myles and my maiden name was Margaret Heaney, we were both from Arklow village and married in Arklow church.

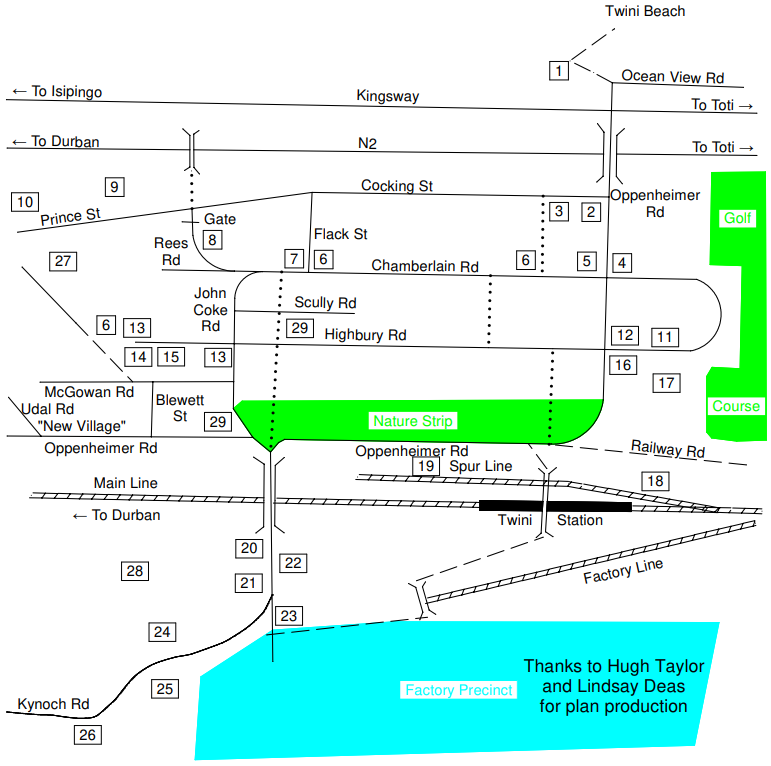

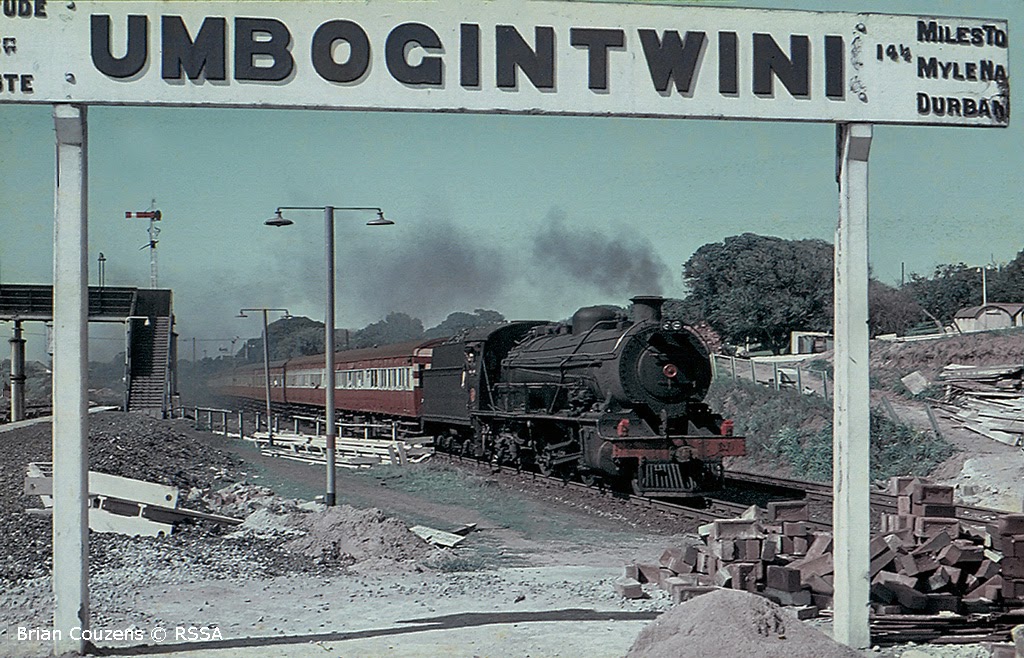

We arrived in South Africa on 29 September 1912. I had one child, Kathleen; she’s living on the Bluff. We lived in Durban for about four months, up on the Berea and my husband came to work by train every day until we came to live in Umbogintwini village in February.

On Christmas morning we all used to go down together to the Hall, the Dining Hall, and they had Mass in it. It was down where the Hospital is now; we never had a doctor at all. The Priest used to come from Pinetown by train.

I had eight children altogether, but there’s two dead. There’s Kathleen, Peter, Michael, Roseanna, Ellie, John.

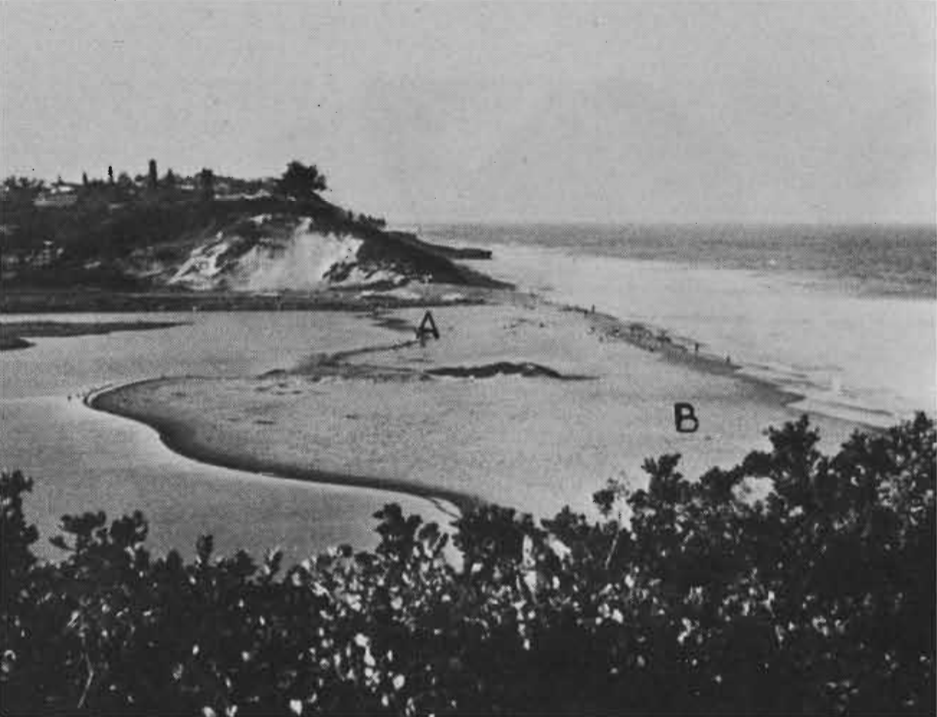

On Sundays we went down to the beach, and nearly every Sunday whole crowds of us and that was our day’s outing, we used to bring a basket along with the children, we used to have a lovely day – all day. One Sunday we went down and a tidal wave came, we were sitting right up on the hill, and the tidal wave come and washed children, shoes, socks, clothes and everything else away, and Ellie was down along with the wave, and only Kathleen, the eldest girl fell on top of her, to keep her from going out. She was only about three years old.

We used to go to Midnight Mass and then we used to come home and go into each others houses and have a little bit of cake and a cup of tea, that was our first Christmas morning.

As told by Mrs Deborah Lee

My maiden name was Deborah Keogh, I was born in Dublin but my mother was born in Arklow and I was married there in St Peter’s church on 5 July 1909. I set sail for South Africa in November 1912 with Bill Lee, my husband’s brother. Our first port of call was Cape Town, we stopped at Las Palmas and Madeira but we didn’t go ashore. We went ashore in Cape Town and we went up on the mountains, all around Cape Town.

We lived in Durban for nine years, Berea Road, Canterbury Grove. We moved from there to Moore Road, a double storey house on the corner, which is a great big building there now, today. There were eight children in the family, six boys and twin girls. The eldest boy’s name is Paddy; he’s the Irish man, born in Ireland.

We arrived in November 1912 in Durban, and I arrived in Umbogintwini in 1921. St Patrick’s church in Umbogintwini was finished when we arrived. While we were in Durban, Pop made a collection for the church and he collected about £60 and that went towards the church and then when we came out here, we bought the carpet, and he made that Christening Font, and there were a few other little things we donated when we came to the village. When I come out here first the Priest was Fr. Verney but the one previous to that, he used to come on horseback, Father Tual, and was a wonderful old man.

There is one instance that really stands out in my mind, in regard to the church and our children, we had a wonderful Confirmation and First Communion, when I came to Umbogintwini, and Paddy my eldest son, he was confirmed in Durban but he was confirmed in Umbogintwini as well! Anyway we had the Bishop out and he and all the little ones had their photographs taken, and then there was the old school there. This was the private house where Mrs Olver is living now, that’s where we entertained, the nuns came out, about 20 sisters, priests and the Bishop. The Bishop and Dr Sormony were entertained at Mr Taylor’s for breakfast. He was the System Manager at the factory. He was not Catholic but came into the church with the girl by the name of May Birtwhistle from home. She was a friend of ours, a lovely girl, not satisfied with this country, she used to teach the children their catechism, was good with the children, very good. She went back to Ireland; she wouldn’t stop here any longer. She took Gerard home back with her and the other little feller, Tom, her two sons.

On Christmas Eve the band would come out. Mr O’Neill, Ned Hughes, Pop, Bill Lee, Bill Roche were all in it. The church was full, there wouldn’t be room, they’d be all outside as well, they would always make arrangements to go to one of the houses, not mine or the others, one of the bosses houses, and they’d stand outside, and the band would start up with Adeste Fideles, and if they were in bed they’d play and shout until they would come out onto the verandah, and they’d bring out the glasses and the whiskey and they’d stop there until three or four in the morning!

There was a very nice choir here at one time but it had died out. They used to pick special choirs, one year it was written by Fr. De Gersigny and we had to go and learn that. Mrs Hayden was the organist here for many years, that’s Mick’s second wife, her maiden name was Laredo, they were French. She trained Kay O’Brien (Hughes) and Kay was over 30 years’ playing the organ. Mrs Hayden played until she got very delicate and they moved out of Umbogintwini to the farm. Some of the Irish people that were here were the Roches, the Hughes, O’Neills, O’Briens, Kellys, Woolahans, Conroys, Kavanaghs, Haydens, Knotts, Doyles, Cunningham, Dinny Kavanagh and Terry Kavanagh. Pat O’Connor was chairman of the Church Committee; he was a storeman at the factory and was married to Mary Kavangh.

He was really good doing for the church. He was one of the best, and he was the one that always called the meetings, and got on with the dances and call any meeting that was wanted, but his main point was to get all he could for nothing out of the factory. He wouldn’t spend the money; he’d like to hand over the biggest sum to the priest of the parish.

As told by Mr Mick Hayden

I was born in Arklow on 19 September 1886 in River Lane and I went to school there in a convent.

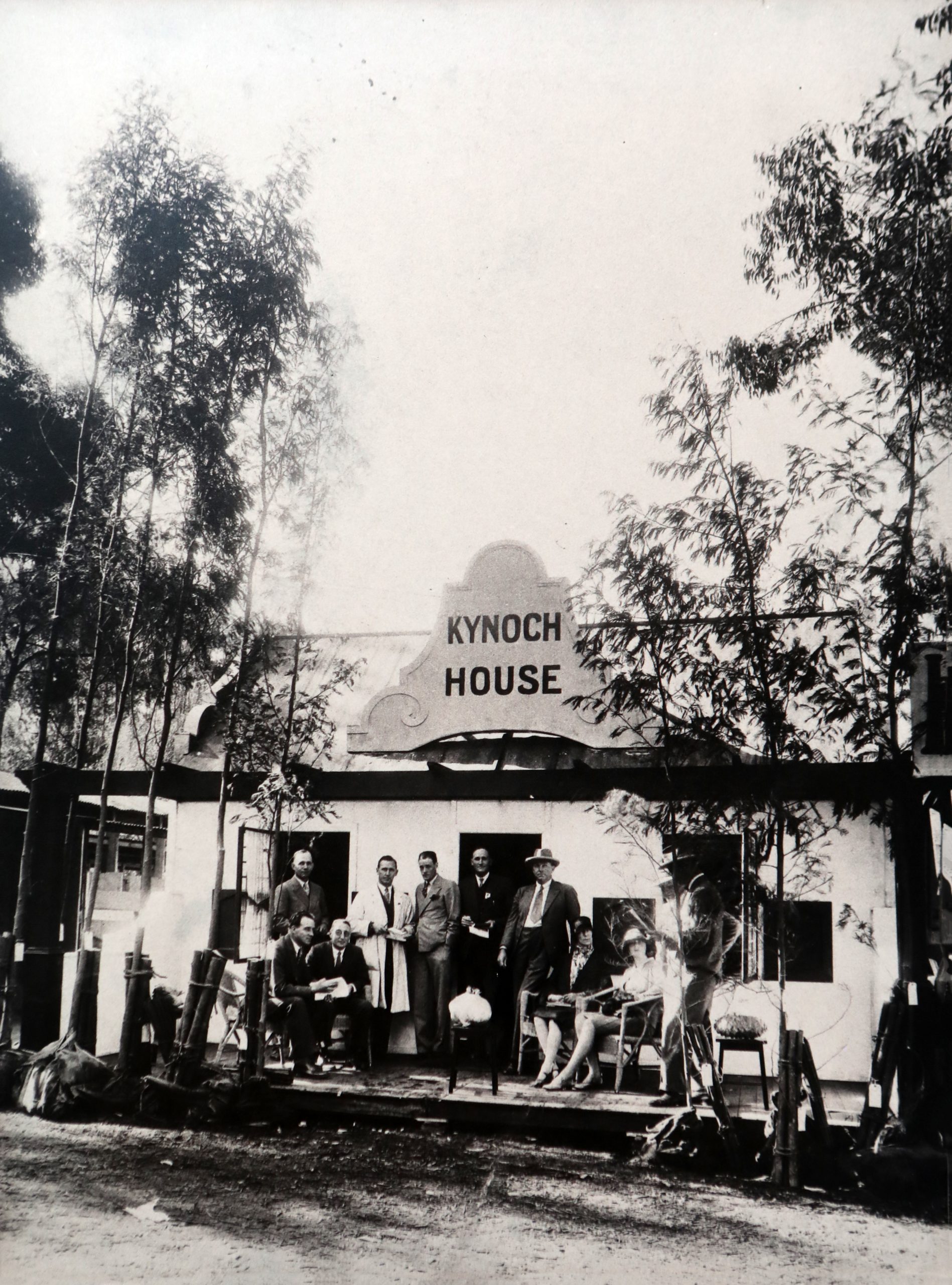

I first received notification of my transfer to Kynochs Umbogintwini on about 1 May 1908 and I sailed from Ireland on 16 May 1908. I sailed on the Munster, there were four ships at that time, the Ulster, Munster, Connaught and Leinster. I sailed to South Africa on the Kenilworth Castle. I came out with Mr & Mrs Campbell, there was just one man in front of us, about a fortnight, a chap by the name of Johnston, he was a foreman ganger. He was born in Birmingham, an Englishman, so I was the first Irishman to arrive. We arrived in Durban the first week in June. My job was foreman plumber.

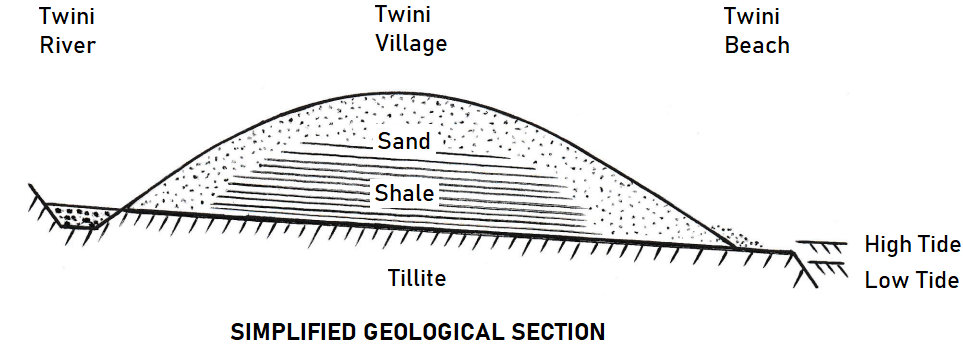

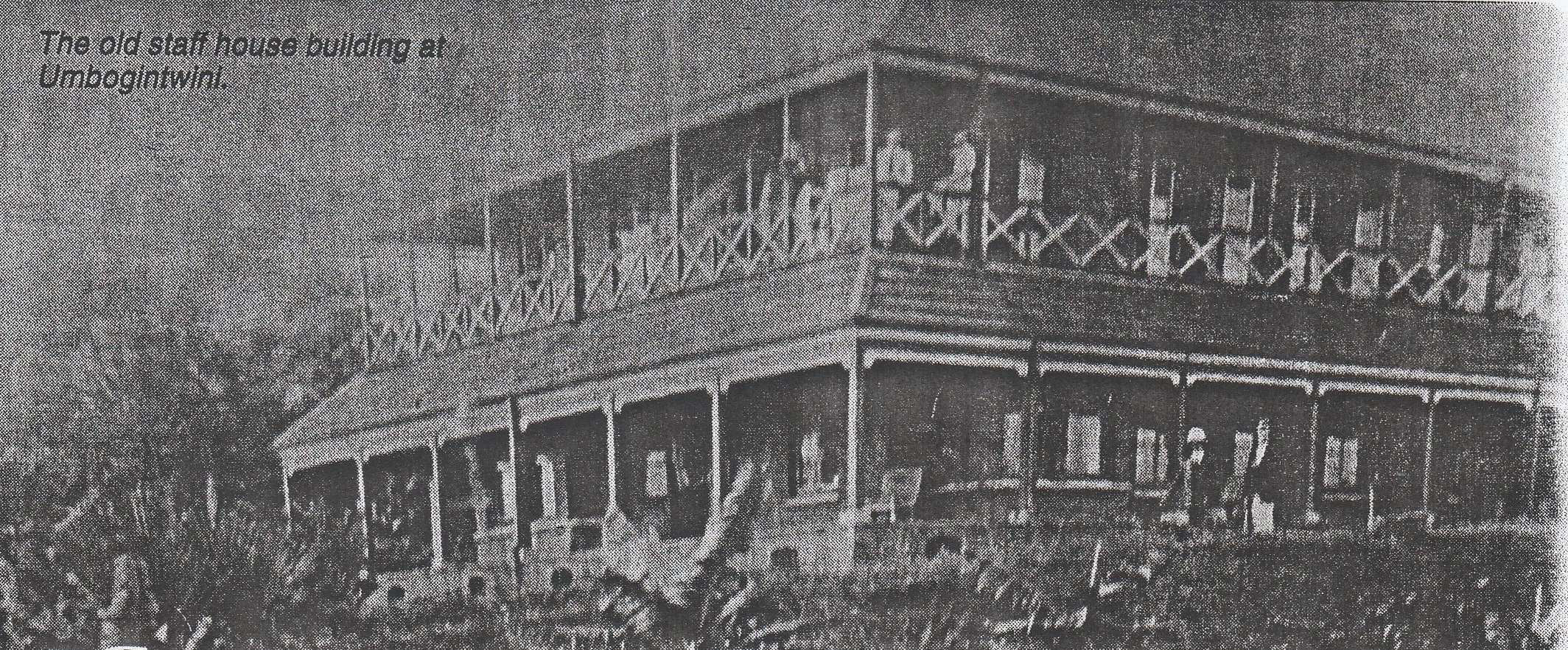

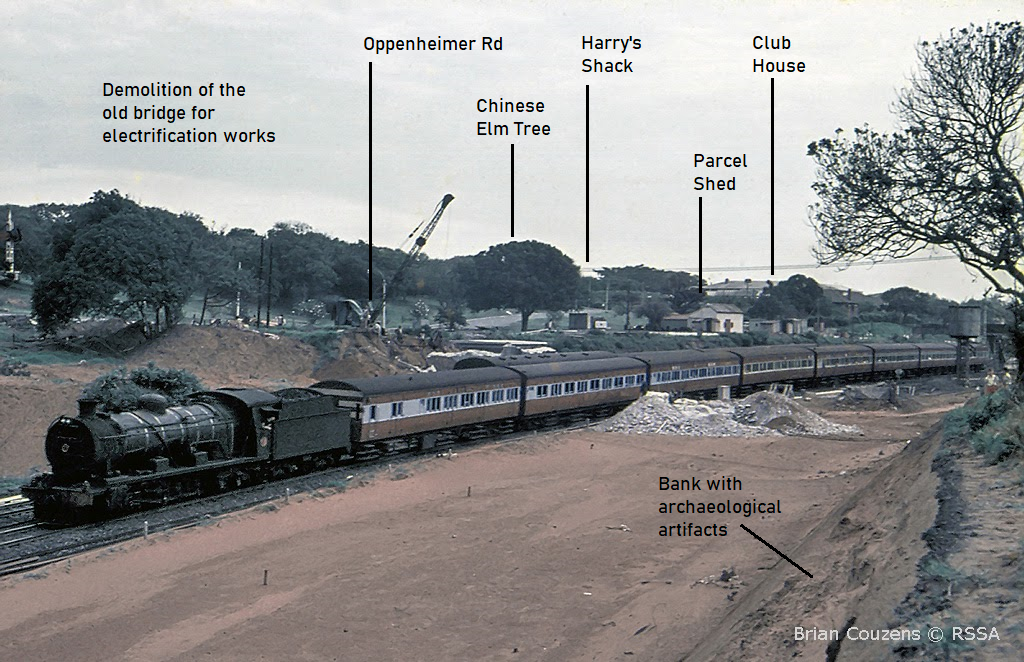

Umbogintwini was complete bush, surrounded by native location, the site had to be cleaned up and preparation had to be made to start building. Building did not take place until about September 1908. There was nothing there, the only thing was a small wood and iron shanty belonging to the Station Master. There was a siding to serve the Africans.

The competition was very keen in those days, between Nobels Modderfontein and Somerset West in the Cape. Manufacturing explosives in Ireland was too costly to transport to South Africa, and compete against these other two factories, so they decided to build a factory at Umbogintwini.

I spent about three months in Durban and after that the factory started to be constructed, I transferred to Isipingo and the first service I had there was in the Railway Hotel, lent to us by the proprietoress, Mrs Creed. The bulk of the congregation were Englishmen from Wigness, but a sprinkle of one or two Irish. The priest was Fr. Mondeu.

We remained in Isipingo for a time until the firm started to build cottages for the working people. The first three cottages were let out to Mrs Roche, Mrs O’Connor and myself. At that time we had to walk down to Amanzimtoti for service. One priest I remember well, Father Tual. Then when the Irish people started in Umbogintwini we had service given us in the eating house at the factory. Then we started to talk about building a church, I was appointed treasurer and secretary, my job was to go around collecting from the Irish people in the factory and the village.

Pat O’Connor and Bill Roche were on the committee and there were fifteen families. The average salary of the Irish working man at the factory per week was approximately £3.10.00 and they offered to give 5/- a week, which was very generous indeed.

We had got an acre of land from the firm, kindly given to us to build a church and a graveyard, but we hadn’t got sufficient money to clean up the grounds. First we wanted a barrow, we managed to borrow pick and shovels, but at that time the firm was preparing a sports ground for the village, so there were a lot of barrows on the sports ground, so Mr Roche thought we could borrow one of those barrows during the night, I agreed. I suggested that we take the barrow up the road, but he decided to take it through the bush. So armed with a rope we went down to the sports ground, collared a barrow, took it through the bush through roots of trees, brambles and everything else, and I can assure you we lost more blood and sweat over that barrow.

Well, we had the barrow alright, and we cleaned the grounds. Meantime I’m collecting in the factory and in the course of my factory duties I had to attend to the office every morning at 9 a.m. to interview the System Works Manager, Mr Taylor. One day he said, “Mick, I believe you’re going to build a church in Umbogintwini. What are the prospects?” “Not too bad Mr Taylor, I’m going around collecting from the men in the factory, I’m getting very generous contributions.” He said, “Well, what security could you give me if I advanced the money to you?” “Nothing but the flesh and blood of the Irish crowd, that’s all I can give you. They’re not paid very well, takes them all their time to live, but they are contributing 5/- weekly. If that is any value to you, well you can give us the money. Mr Taylor, why are you so interested in building a Catholic Church?” “Well, I’m courting an Irish girl in Arklow and I want to marry her, and I want a nice little church built for her by the time she comes to Africa, if she is to be my wife.”

I said, “Mr Taylor, don’t you think you are risking a lot, there are no Catholics in Umbogintwini except the Irish crowd, and they are all of poor working class, you are amongst the staff and they naturally will look down upon you if you contribute that money.” He said, “I’m going to do it. I have no religion, I may have had one, but I’m not even a bush Baptist, and I want to become a Catholic with my wife.” He gave us the money and we arranged with a contractor for the sum of about £1800. He advanced us the money in full. We worked hard and repaid him in 18 months from the time we borrowed the money. Mr Taylor’s fiancée was Miss Birtwhistle, they were married in Arklow then came to live in Umbogintwini where she taught catechism.

Contractors got on with the job very quickly and were making a nice job of it, but the guttering and everything surrounding the church was not in the contract and I was the only mechanic on the Irish side, but I had about eight Scotsmen working with me and I asked them if they would give me an afternoon on a Saturday to complete the guttering, water downpipes, etc. and they agreed. So they all turned out in a body and did a thoroughly good job of this, and refused to take any payment.

Well, the church was completed, we were having service, quite comfortable, we organised a choir, my wife as the organist, and Dr Sormany as instructor, but one thing we did lack was a bell. There was a real nice bell on the sports ground, only used once every year, so Roche, he was in a sentimental mood, thought we should have a bell, I agreed. So we went down to the sports ground and collected the bell and took it to the church. The following Sunday morning the bell rang. Amongst our congregation was a Mrs King, married to a Scots Presbyterian, who was our Chief Engineer at the factory. He brought Mrs King to church. He saw and heard the bell and said, “Mick, that’s a nice bell you’ve got there.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “It’s got a nice tone.” “I agree with you.” “Where did you get it from?” I said, “We had it in pawn ever since we arrived in the country, we’ve just redeemed it now.” He knowing perfectly well where the bell came from however. We had the bell for a year and then the day of the annual sports, we returned it.

Now in the course of going round collecting, there was an old Irishman by the name of Nobby Clark, who spent every penny he got on Friday afternoon on Friday night. I thought there was no use in going to Nobby, he will have nothing on Saturday morning, but this Saturday morning I felt someone tapping my shoulder. I looked round and there was Nobby Clark. He said, “I’m surprised and disgusted, I believe you are going around collecting money for to build the church and you never come near me.” “But,” I said, “Nobby, I didn’t think you would have anything to give on a Saturday morning, in fact you are always borrowing. He said, “Here’s 10/- for you now, and come back every Saturday morning.”

A little later on I met the System Manager, Mr Blewitt, who was an Englishman and I assume an Anglican. He said, “I believe you’re going to build a church in Umbogintwini?” “Yes we are.” “And what prospects have you?” “Very good indeed.” He said, “Well, here’s 10/- towards it.” I said, “But Mr Blewitt you’re not a Catholic.” He said, “No, I’ve got a good friend in Fr Verney and this is my first subscription to it.” I went further on an met the Anglican person who was at the head of the Anglican church at the time and he passed a funny remark, “I don’t know what’s wrong with Mr Blewett, I can get no help whatsoever for our church from him.” I said, “I’m surprised, I have just received 10/- from him for the Catholic Church!”

The church was built, we wanted an organ and we wanted a few statues. Mr Taylor kindly presented us with the organ and incidentally I presented the chair for the organist. Mr Taylor went home to be married and he brought two nice statues, one for himself and one for me, St Joseph and the Blessed Virgin Mary.”

To pay off the money we owed Mr Taylor, we organised jumble sales in the compound and went around collecting everything we could from the village people. I loaned an ox wagon from the firm and brought it down to the compound, and amongst the lot was a box from the factory. It was given to me from the factory leaving Ireland, with several broadleaved shamrocks on it. Well, I haggled with the natives and sold everything but the box. I looked at this and wondered whether to part with it, thought it’s for a good cause, I will. I got exactly a pound for the box and thank goodness the money was paid and the church was quite free and for years we had a lovely church there and we had some lovely Fathers there.

Besides the jumble sales we had bazaars and dances. We had joint bazaars with the Anglicans, the Anglicans supported us very very well indeed, they gave us all the help possible and the funds were equally divided between the two bodies. The income from the first jumble sale in the location was £25, and from the bazaars between £7 and £12, they were held about every three months. The total sum raised came to something like £300, one sixth of the whole cost of the church. The Umbogintwini people are still famous for their generosity.

We collected £5 for every St Patrick’s Dance we had. It cost us nothing to run because the ladies of the village produced all the refreshments and whatever we gained there was a nett profit. The dance was first held the year the church opened. The church was blessed by Bishop de Lalle and the ceremony was also attended by two young Irish priests. I remember meeting them when we were examining the Foundation Stone.

My first wife’s name was Frances Manifold, Fanny. I was courting her in Arklow about seven years before I left and she could not live without me and all, so she came out to South Africa as a friend or servant of one of the managers and we got married here. But we were only married about nine months when we had an explosion and the shock killed her. Eleven people were killed in that explosion, including one Irishman, Mick Kelly.

The Irishmen who formed the first group were Mr and Mrs Campbell, Johnson and myself. The second group were Paddy Cunningham, Pat O’Connor, Jack O’Neill, Charley Travers, Mick Kelly, John Joe Kelly, Dick Knott and Mrs Knott, Myles O’Brien, Dinny J Kavanagh and Paddy Kavanagh, Charley Gilbert as near as I can remember, but there were others who did not come from Ireland but came from England.

We heard that there was a famous Irish priest in Durban giving a mission by the name of Fr. Hayes and we thought we would like him to come out to Umbogintwini. We went in and interviewed Fr. O’Donnell who was then parish priest of Durban. He said that Fr. Hayes was too tired and could not undertake a journey like that so we pushed our way beyond Father and went and interviewed Fr. Hayes. He definitely was a tired man but we begged him, persuaded him to come to Umbogintwini. He came, he gave us a lovely mission and got so fond of Umbogintwini that he did not want to leave it.

Amongst our supposed congregation was a man by the name of McLaughlin. McLaughlin went nowhere; he always professed to be a bush Baptist. Fr. Hayes heard of him and went and saw him. McLaughlin promised him faithfully that he would attend service that night and go to confession and have communion the following morning. McLaughlin never turned up. Well that night Fr. Hayes gave us a sermon but before he did he made a remark, “There is a man amongst you crowd by the name of McLaughlin, who promised me faithfully that he would come to church to confession and communion. He has not done so. I want you to punish McLaughlin the same way as I would punish Lloyd George, the Prime Minister of England, give him the whip!” Now Fr. Sormony was on the side altar, he kept pulling Fr. Hayes coat to remind him that McLaughlin was in the church. “All the better, he hears me now he’ll come to his senses.”

The following morning Fr. Hayes and Fr. Sormony was out for a walk, they met McLaughlin. “Why did you not fulfil your promise?” “I’m sorry Father.” “Will you come tonight?” “I will Father.” “Come to confession and communion?” “I will Father.” McLaughlin was there that night and confession and communion the following morning! The mission was a terrific success and Fr. Hayes felt quite at home with the crowd, it reminded him of home and we had a job to get him to leave. In fact we were compelled to say, “Father, if you don’t go we will never be able to welcome you back.”

My second wife’s name was Noël Laredo, she came from Tasmania, Australia. She was three quarters Irish extraction and one quarter Spanish.

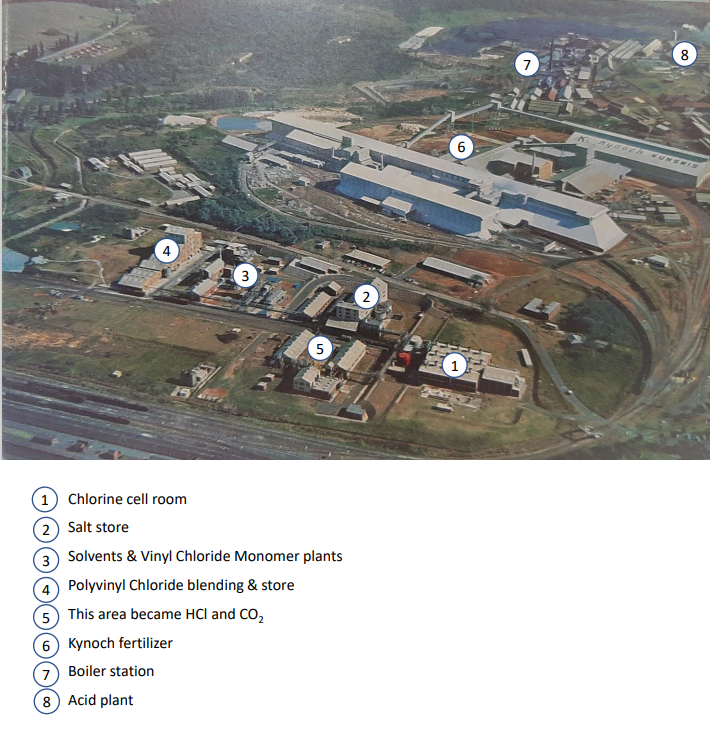

When I arrived in Umbogintwini there was nothing but bush, in fact there was a native location, and we had to start cleaning up to prepare for the buildings being erected, we had to work very hard to get this in a fit condition to erect the factory. Eventually we got going but before, we had to apply to England for a crowd of leadburners to build our sulphuric acid plant. About 50 men came out from England, from a place called Wigness, at least 60% of them were of Irish extraction and fairly good Catholics. There was Jack Townsey, Jack Rider, Tommy Duffy, Bob Jones, Bill Handly.

The first manager of the new factory was Mr Udal. He was an Englishman who really came from Arklow to start the factory at Umbogintwini. He was a manager in Arklow and where there he met me on the quay-side with my father and he seemed to take a liking to me and he asked my father if he would allow me to go as an apprentice to him. My father definitely agreed because he could get very little good of me going to sea, so he thought I would probably settle down in a permanent job. Eventually we agreed on conditions and I was taken before a magistrate and bound for seven years under the management of Mr Udal with the firm Kynoch Limited, which was then well established in Arklow. Well there was a foreman there by the name of Steward, a north of England man, who also took a liking to me. He was about to leave Arklow when I had just about finished two years of apprenticeship, he asked me if I would go to England with him. Well, I agreed, unknowing to my people. He went to a place called Stonemarket in England and after he’d settled down there he wrote to me to come there with him, but my brother, who was then foreman at Arklow, interfered, called my father and mother together and they decided that I should not go, but I still insisted that I wanted to go. Well, I was taken before Mr Udal, and I was definitely told that I had signed an agreement with him, that if I did break the contract they could put me in prison, so I had to settle down and complete my apprenticeship of seven years.

Three months before my apprenticeship was up I had definitely made up my mind to go to America where all friends were and I set about saving some money for the trip. I worked night and day to collect £50. in the meantime Mr Udal had disappeared, we did not know where he had got to, but somehow or other, the System Manager, Mr Hoyle, a Yorkshire man, heard that I was preparing to go to America and he interviewed me, said I was a young fool to attempt to leave the factory.

I told him, “Well, I’ve learned all there was to be learned at Arklow, and I want to seek fresh fields of adventure, so I thought America would be the best place to go to.” He said, “No, don’t do anything rash. Mr Udal has got something in his mind for you.” I said, “My apprenticeship will be finished the end of June, and unless you tell me what Mr Udal wants for me, I’m definitely preparing to go.” He said, “No, Mr Udal will be here next month, that be 1st May.” So Mr Udal came eventually, back to Arklow, and he sent for me. He told me he wanted me to go to South Africa, a place called Umbogintwini on the South Coast. Well, I asked him what the country was like and the conditions. He said, “Well, you can get a suit of clothing there for 15/-, that’s very cheap.” We were paying something like £3 to £4.10.- here for a suit of clothes. He wanted me to take charge of the construction work at Umbogintwini, and I though I was rather young because I was only then 21. He said, “Well, it’s for a repeat of what is in Arklow, and you know exactly what has to be done there, seeing you have served seven years apprenticeship here, and you have supervised and did a certain amount of construction in Arklow which will be the same as what will take place in Umbogintwini. I definitely refused. I thought I was too young; I wanted to see the country first, to see the people to see I liked them before I would settle down. We eventually agreed that I would be in his hands for six months, and he would employ a much older man than I to take charge of the construction, so I came to Umbogintwini.

When I went to look for clothing, I found that instead of paying 15/- for a suit, I had to pay £4.10.-. The suit of clothes that he referred to was cotton duck, really what the natives used in kitchen work!

However, I was still leaning, pretending to be quite ignorant, getting their views, and the idea of the work from those Wigness men from England, and it was rather a hard job keeping my temper, but eventually I decided that instead of going to the Tech, I would go to a boxer by the name of Barney Malone, who was a real good old professional man of Irish extraction. I was with him for six months, being trained privately at night time.

In my work at the factory I got very little free time, we knocked off at 5 o’clock and we had from 5 o’clock until 7 the following morning, that was the only time we got off.

As far as I can remember there were 11 explosions in the early days. The first took place shortly after we started the factory, a young man by the name of Mick Kelly from Arklow was the only casualty so far as the Irish crowd was concerned, certainly a few other Europeans and some natives. That was the only time that I can remember that any of the Irish crowd was killed and I must say that it was not through any fault of his, or the fault of any of the Irish men that other explosions took place, they were all off-shift at the time, not once did an explosion take place while the Irishmen were on shift.

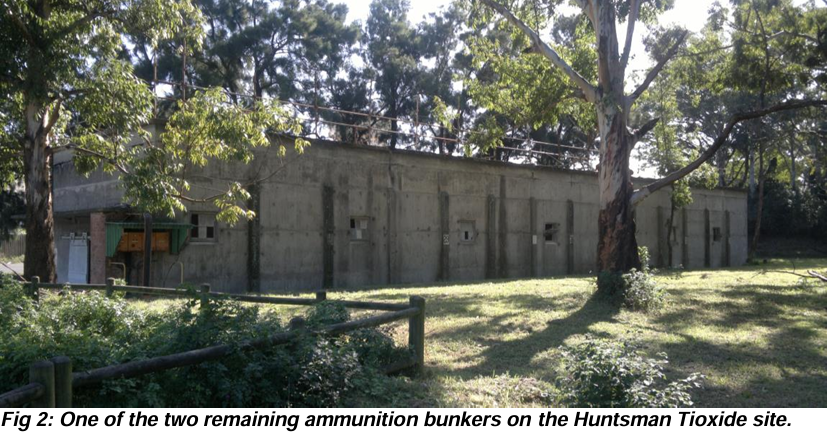

I heard about the explosion that wrecked Kynochs in Arklow in 1917 from home. I spoke to one of the managers who came from Arklow to Africa here, a man by the name of O’Gorman. I asked him if there was any truth in the explosion that took place, was through the cause of the Irish rebels, and he said definitely not, there’s worse people in the factory than the Irish rebels were, and I must say we had the same experience at Umbogintwini in 1914, when war broke out we were certainly sabotaged at Umbogintwini. Our principal sulphuric acid plant was burned down.

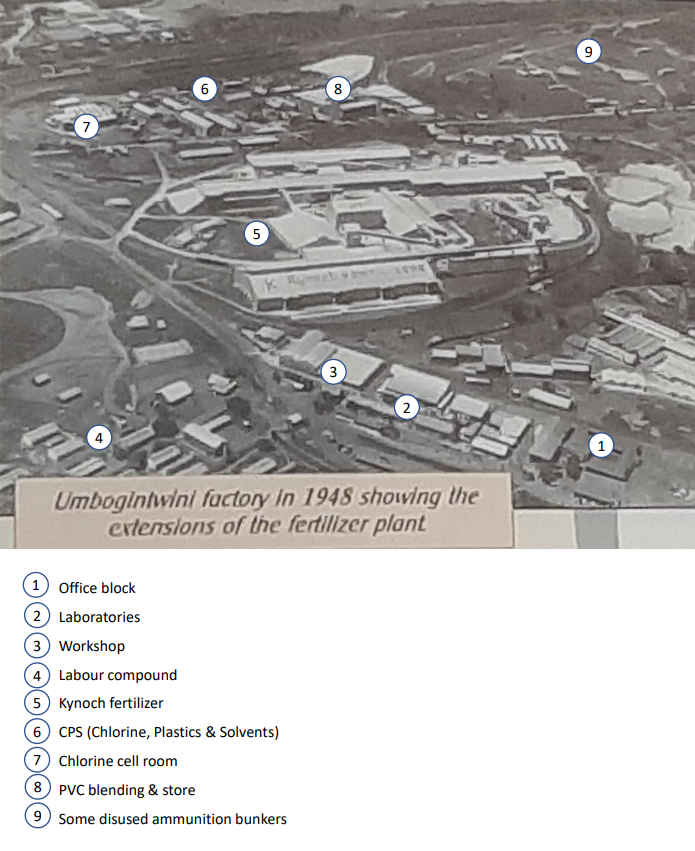

The man who came after Mr Udal was Mr Helke, he really came to close the factory down. The principal reason was that they were about to become amalgamated with Nobels, a Scottish firm under the chairmanship of Sir Harry McGowan, and also the prospect of becoming amalgamated with Somerset West. Mr Helke came really to dismiss the best part of the employees and under instructions from overseas he recommended Mr Blewitt as manager. At that time we ceased to manufacture explosives and we had just started manufacturing small sidelines, fertilizer certainly was coming to existence, but we had not managed to obtain the contracts for fertilizer at the time, so other small items had to be manufactured to keep the skeleton staff going. The factory ceased to manufacture explosives in about 1924. At the time that the church was built somebody said that there must have been close on 100 children from about 25 families.

We started playing hurling in the early days. Bill Roche and myself started, and then we incorporated Pat O’Connor, Tom Kennedy, Ned Hughes and several others. We’d quite some lively games and eventually they started a club in Durban and I must say we’d quite a lively time with the games played between the two clubs. It was lovely to think that one could play the game that one had followed from childhood up, and everyone thoroughly enjoyed it. I think the reason why it was given up was all the old hands got old, and were unable to follow the game, and the younger didn’t follow the game as it was too much like hard work, so it eventually disappeared and all those youngsters went to cricket and football.

As told by Mr Jack O’Neill

I first came to the South Coast of Natal on 28 November 1908. I was about 28 I think. I came from Main Street in Arklow, in the town itself. There were 18 of us coming out on the ship, and two women, Mrs Roche and Mrs Knott. When we first came to Umbogintwini we stayed at the Royal Hotel in Isipingo for a few nights, and then we went down to Amanzimtoti and then back to Isipingo. There was no Umbogintwini then, no village, just bush. We had to walk from Amanzimtoti to go on shift. It was a long walk at night, midnight. In those days the people were a bit civilized, there was no danger in walking out at night. We ran the first charge of nitro glycerine here when it started.

Mr Taylor took the leading light in the building of the church. He was wonderful, put all his heart and soul into the church, and his wife took a great interest in it. He was a superintendent down there, a convert who married an Irish girl, Birtwhistle. There were quite a few people living in Umbogintwini then, about 20 families, the majority of them Irish, the children went to St Josephs in Durban. The church was begun in 1917 and finished in 1918.

I was married in 1915 at the Cathedral in Durban. My wife’s name was Ruby Reynolds, we had five girls and three boys, we did lose two. Six left.

As told by Mrs Kavanagh

My maiden name was Martha Mary Redmond. I was married in Durban at the Emmanuel Cathedral by Fr. O’Donnell. I arrived in South Africa on 5 March 1910, I came over quite alone, on the German Castle. The trip took one month, we had a very nice time on board, plenty of fun and dances and when we arrived in Cape Town we went to see the sights at Cape Town and then we carried on up to Durban.

I was met by my fiancé then, I arrived on the 5th and was married on the 6th March and I came out to Umbogintwini on the 4.20 train. My husband was very sick, he had been dad with dysentery and he was ill for about a fortnight. His name was Dennis Joseph and he was from a place called Castletown, about 16 miles outside Arklow, I was born in Tinahask, in Arklow.

When we arrived in Umbogintwini I felt at sea there and I cried my eyes out for to get back home, yes, it was nothing but bush, the bush was right over our heads, it was terrible. I remember there was some people at the back of us by the name of Whitfield, and a lot of people used to say to me about the snakes. I said that I’ve been here a week or so, and I haven’t seen any snakes, so my husband said, “Well, the next one we hear about, we’ll let you see it.” Well, anyway I heard a shot one morning and I ran in to him and said, “Somebody must have killed a snake,” and I went through the back door and saw Mr Whitfield, who was a patrol in the factory, and here he was coming down the road with a terrific big snake with a rope around its neck and a dog in its mouth, and he said, “There’s a snake for you now, now you’ve seen a snake.” I said, “Well, I don’t want to see any more snakes.” Oh, they were killing snakes every day, they were shooting them in the trees in the gardens and everywhere, but funny enough there was nobody bitten by one. Yes, we had snakes galore in Umbogintwini, there was nothing more plentiful than snakes.

There were eight children in the family, James, the eldest, then came the twins, Stanley and Redmond, and then Willie, Eileen and Lorraine. They’re all still alive, even the terrible twins! Oh, I tell you, I had a real pantomime with them sometimes.

I remember the forming of the committee to build the church but I was busy with the youngsters being babies, you know. There wasn’t much difference between them, they were all like steps of stairs, as they say, and they kept me busy, but I remember the committee and all they had to do with the church. That was the first thing we thought of when we arrived out at South Africa, was a church, and we got the church going as soon as we could, and the priest used to come out on a motor bike and we used to have a service in the dining hall at the old club, down by the time office you know.

I remember one explosion particularly well. I was on my way out here, when my ship arrived in Cape Town I heard more about this explosion, and when I arrived in Durban of course I heard all about it. My husband told me that they had a very big explosion. He had a house ready for me on my arrival, and as he hadn’t been too well, he shut up the house one afternoon and he went for a walk and at the railway station he heard a bang and he looked up and there was a house exploding in the sky, so he got a fright, the hooter went, and there was a lot of excitement, and he said the first thing he did was he went down to the factory to see what had happened. Then he had closed up the house, thought he ought to go back to see what had happened to the house, and when he got back there was a paraffin oil lamp that had been hanging down in the middle of the dining room, and this had fallen down, the oil was all over the table cloth, all the delft in the kitchen was on the floor, the windows were broken and the place was in a proper mess. However, we were lucky, any damage that was done to the houses, the company made it good, so that was my first experience of an explosion in Umbogintwini.

As you know the 5th November is Guy Fawkes night. Well in the day time I had gone to town and the twins had told me that they wanted coloured matches. I said alright, and when I came back I had the coloured matches for them, but I said “You’re not to have those matches until the night, because it’s no use in you lighting them in the daylight.” They said, “Oh Mammy, let us have them, we won’t light them until the night time.” So of course, being a weak mother I let them have them, and I heard no more about the matches until late in the afternoon. I heard that something had happened at the Club, there was a fire. There was a kind of a shed there, a thatched shed where the golf club people kept their tools and machines for mowing the golf course. So this golf course hut went up in flames. Apparently the twins had gone into this place, being dark, and they wanted to see the coloured matches lit, and they must have lit them, they caught fire and up went the shed, and away went the twins. Nobody could find the twins, and I don’t think to this day that they knew who set the place on fire. Anyway they ran home and into bed and covered themselves up and I didn’t know anything about it for months afterwards and had I known then they would have got a darned good hiding. Being boys, you know, they were always up to mischief.

I was taking the family down for a Sunday School picnic to Kelso beach. The train was going 8 o’clock that morning and the night before I pressed the twins’ new little sailor suits and put them on the box beside their bed, for to be ready, for there was quite a few of them to be got ready in time. When I went to call them in the morning, here they were in bed dressed in their sailor suits, and I had to get them up and press them again. They had got up during the night so that they would be ready to get the train they got up and dressed themselves in their clothes, and went back to bed again and fell asleep.

As told by Mrs Roche

I first received word that I was coming to South Africa when Kynochs put a notice up calling for volunteers to go out to Africa, and as there were hundreds of applicants, they picked about 15 men and three women and we were one of them. It took me a long time to make up my mind, but as Bill was going I went with him. My mother and them wasn’t terribly pleased, because they thought it was a black man’s country an when they tried to put me off, not to go, wait till I see that he’s send messages and what kind of country it was, and if he was doing alright, and if it was possible to stand the climate. The climate was the whole topic of conversation. Anyhow, I went with him and I was jolly glad I had his help on board ship because I was sick from seasick, pregnancy and homesick. I paid £18 for my fare and Kynochs gave us £5 to spend on the voyage out.

We were married in Ireland in the same church that my mother was married in, where I was christened in, by the same priest, Fr. Dumfrey in Arklow. My father built the national school in Arklow and was very well known and his sons have taken his place there. My maiden name was Ellen Mary Kavanagh.

We left Ireland the last couple of nights in October and arrived here on 22 November 1908. My first baby was born in the bush without nurse or doctor seven months later. This was in Amanzimtoti, there were about six houses there at that time but there was none in Umbogintwini, they were getting them ready quickly, and about another year I moved to Umbogintwini. They had built the first six houses. There was a few wood and iron houses before that belonged to Kynochs, one was for the compound manger and one was for the man who was running the dairy and another for a fitter. We got the chance of buying that one for £60 and we didn’t take it, but after that Kynochs gave no more grants and land, they built the houses themselves so we went into one of the six that was built.

Holy Mass was said in a person’s dining room down there by the name of Hughes, near the Riversea Hotel, added on to and improved and when it was said in Mrs Knott’s dining room, another Irishwoman who came out with me, then we sometimes had it in Umbogintwini. My child was christened in my own home by a little priest who lived on the Bluff, and he came over when we sent for him. A priest used to ride from Mariannhill across country for to say Mass for us, on horseback.

My husband was one of the leading lights in trying to build the church, they formed a committee and about eight people who went on the committee consistently kept the collections up and went round every week. The men were paid by the week, they got the collections from them and then Bishop de Lalle opened the little church for us. My husband was the altar boy and sang in the choir. He used to be secretary of the Catholic Church and Secretary of the Building Society and they presented him with a lovely silver cigarette case for services rendered. He was chief cook and bottle washer up there one time!

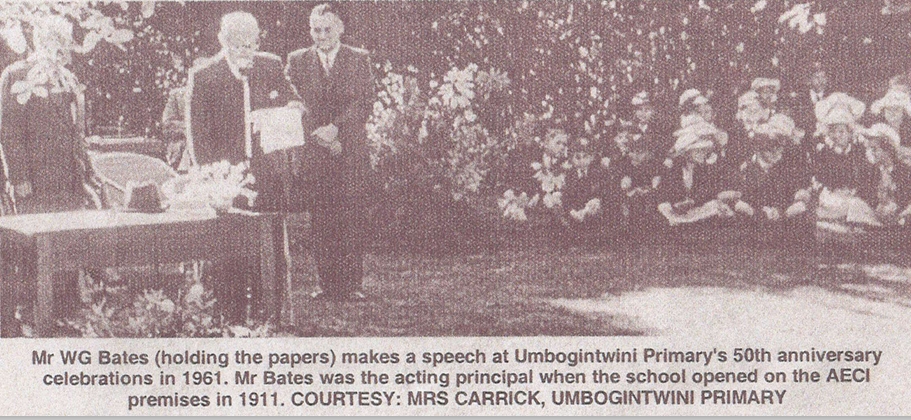

A Mr Bates, the school teacher, helped such a lot, he was delighted to see a Catholic Church go up there. He gave me £1.10.0 towards it one day, he was not our denomination. He helped my husband lay bricks outside and lots of people such as Reverend Skelton who used to be a minister in Maritzburg, he never passed by without coming to see how the church was going on, and was delighted.

Every denomination helped, if there was a bazaar or anything, we all joined in and shared the takings, there was no bigotry amongst the people at that time. A man called Brown from Umkomaas built the church; it was very cheap, about £600 at the time.

We loved it in the old days, the people were so united with each other and we had to make our own amusement and any occasion was good enough for a party, a Christening, wedding or birth, or anything there was a big party always. Everybody had to tell a story or do something in the party, we had generally Mr Lee and Mr Kavanagh being master of ceremonies and they insisted on each person doing something.

We were very short of something to do in the beginning, so the men decided to ask permission to build a handball court, they had never heard the name of it out here, or seen it, but the crown in Kynochs gave them permission to have a court, and they helped them to build it, and they also, after a lot of urging, each person paid an initial subscription, they made six holes of a golf links, which we knew every blade of grass on before we finished with it. That was the beginning of the Umbogintwini Golf Club and the beginning of some grand players. The young Irish fellers excelled at golf, surprised people how well they could play. But the handball court was a beautiful court, and then we had hurling. There was lots of hurlers amongst the crowd what came out and they sent home to an aunt of mine who sent out the sticks and some 12 dozen half solid balls to play hurling with, and they called themselves “The Shamrocks” and a team started up in Durban in opposition to us called “The Exiles” and they was great hurling, and there was lots of accidents and split noses. Mr Hughes had his nose split one day in Kynochs and had to be taken to hospital. The people here couldn’t understand the wild Irish game, it is a game that if played to the rules there’d be no accidents. If they have a spite against you they can bring it out in hurling alright.

I am very proud that my husband Bill picked the site that St Patricks is built on. Kynochs gave him the plan of the ground here and he picked that site himself, up on top of the hill, but gradually the village crept up to it, but it was a nice quiet place. Every St Patricks even if we didn’t make much, the company always contributed towards our dance funds, but the dance was a recognised event, of the South Coast with the generous refreshments, good music and good fun. Everyone went to the St Patricks dance, it was a well-known dance all along the South Coast.

When we first came out we walked down to the beach to Amanzimtoti on Sundays, came back on the train for 6d. There was no club at the time, club was built a couple of years after we were in the village. There was no motor cars. There was one motor car in Durban, when we landed there, and there was no trains out of Durban after 5 o’clock at night. Kynochs built a big place down there like a sleeping quarters, and the men got off the train at 5 o’clock and went and got into bed and were called at 11.30 to go onto shift work at 12 o’clock. That went on for years. It was where the hospital is now, there was a big hall up there used as a dining hall, part of it in the day time and the men had lunches there, it was run by the people who had the boarding house in the village, Humphreys, and another man called Gordon ran it. He was working in “B” house in the factory, and they put him in charge of this dining hall, a grand cook, and an old man, and that’s where we held our dances in the beginning, in that hall. I happened to be one of the first who had a gramophone, and the young fellers in the village used to come and borrow my gramophone and borrow me too and take me down with the horn on one arm and the box under the other, and we had dances, and we all had to pull the fellers up, they were shy, but they wanted to dance, and that was our amusements down there. We had concerts there, and one night we had such a laugh at the concert that a woman, actually the first woman in Umbogintwini, Mrs Weller, who has lately died, she laughed so much she went into hysterics, and we had to carry her out. I forget what it was about.

After a little while there was a school built for us. Before that they went with us to Isipingo on the train. There was a friend of mine and another man hired their own teacher and they started with a room down there in the old hall, at Amanzimtoti, some children went down on the train there. Most of them went to Durban, St Josephs.

At first in 1908 about 10 people came out, two or three weeks before me, then the next lot 15 came, 10 men and five women, some were sent back home with suspected TB and different things, and there was a depression at Kynochs and some of them were told to leave and they went home. I know all that came out with me on the boat. There was Mr & Mrs Knott, Mr & Mrs Metcalf, Mr Bill Murray, Harold White, Mr DJ Kavanagh, Mick Kelly, Paddy Kavanagh (Mick Kelly was blown up in our first explosion, my husband was in that explosion too, he was blown up and hurt on the hip), Mr McCull.

Reference: South Coast Sun, 3 July 2008

Reference: South Coast Sun, 3 July 2008

![DSC00008[1] DSC00008[1]](https://www.umbogintwini.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/DSC000081.jpg)

Hi, will send some Twini news in my possession rgds. Marianne Chelin

My earliest memories of the Twini Village are of our family living in a semi detached in Oppenheimer Rd for a few years. I was living there when i started school at Umbogintwini Primary in 1971.

We then moved to 29 Highbury Rd, where I completed my schooling at Kingsway High in 1982. I lived at Highbury Rd until 1985. I married Neill Lovell in March 1985 and we had our reception at the Jubilee Hall. My parents, Robin and Val Roberts lived in the same home for 38 years, until they were forced to leave because of the sale of the village. They were the longest standing residents of the village.

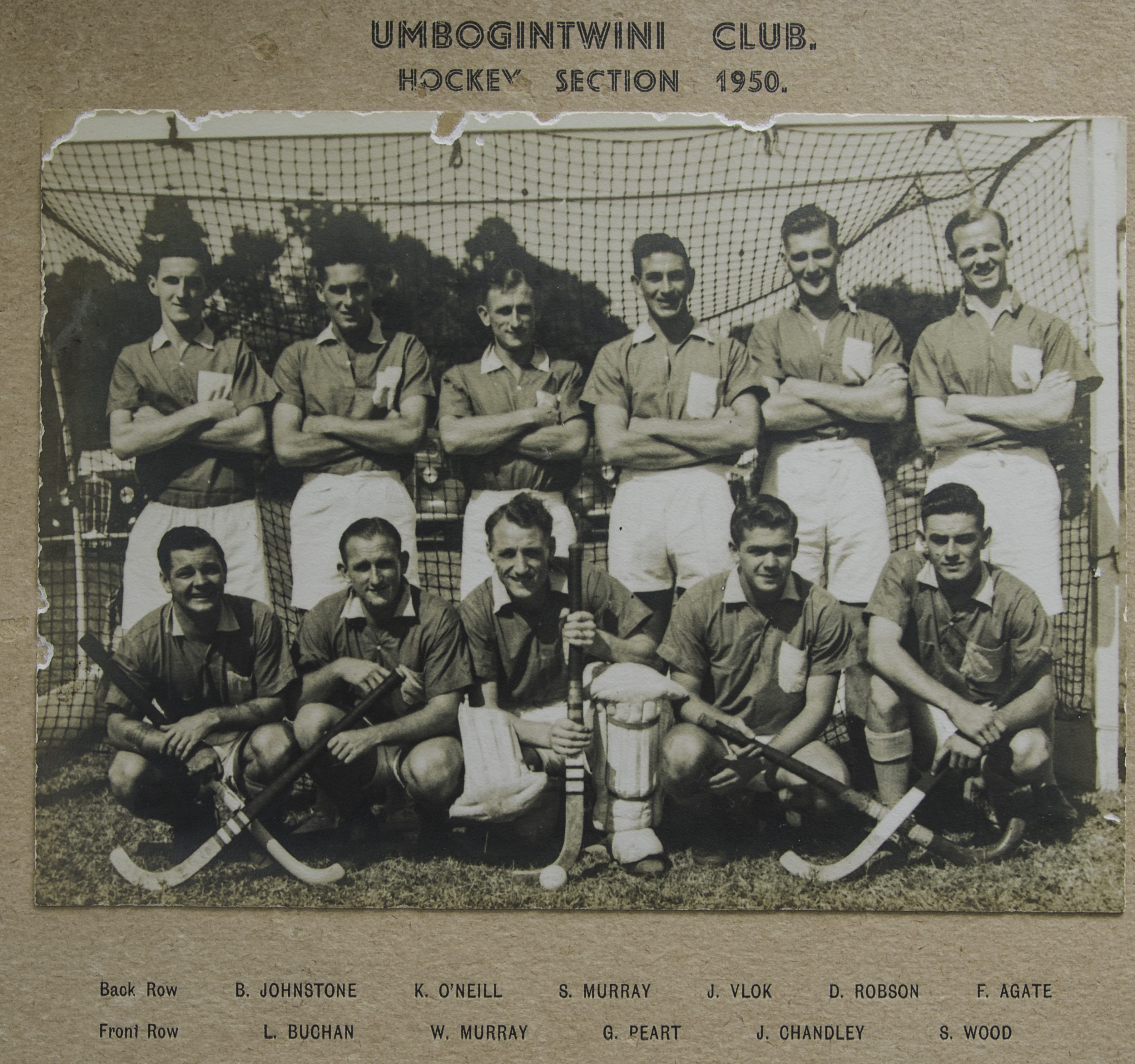

Well known family names I remember clearly are Kenton, Kelly, Grubb, O,’Neill, Wheeler, Prinsloo, Nortje, Northmore, Buchan to name a few.

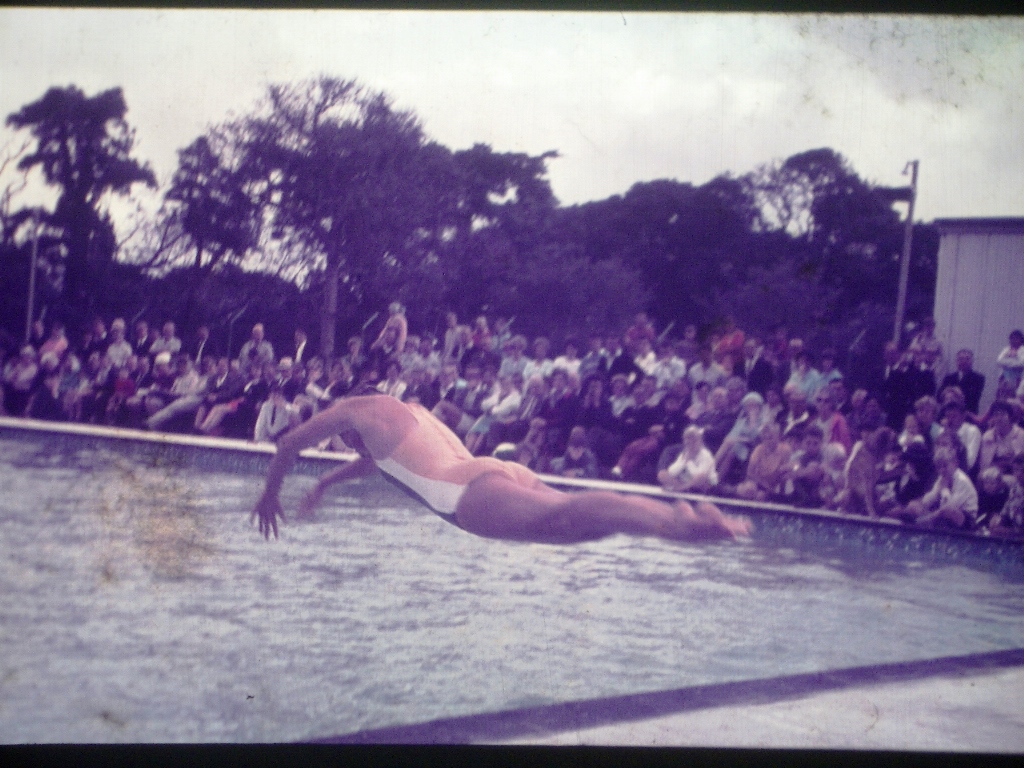

We had a carefree life there, playing with friends until the early evening and being able to walk home alone. Going to the club swimming pool in the holidays. Catching the train to school. Going to the club to watch my dad playing his last hole of golf. Watching tennis matches. Music productions at the Jubilee Hall. I could reminisce for ages.

Thank you Twini Village for the memories.

Good Evening Leigh- Anne, I currently live in the Village in Oppenheimer Rd, called Arbour Village. Been here since 2010. Do you perhaps have pictures of the old village. Would be interesting to see

I also attended Umbogintwini primary school. In 1975 , l was in std 5 and wonder how many students are still alive? Mr. Willis was our class teacher and l wonder also about him. I would love to hear from anyone of class ’75.

Hi Johan

Without your surname I am finding it difficult to place you. I very well remember teaching at Umbogintwini Primary and thoroughly enjoyed my time there.

Of course a lot of time has passed since then. I am now retired and living in the Netherlands. I have two children who also live here. We have all been here for 21 years. The country has been good to us and we are very happy to be here.

I hope you are doing well and would love to hear how life has treated you since 1975 .

I was born in August 1960 when my parents (Pat and Trevor Elliott) lived in Highbury Road. My younger brother by 2 years, Glen, was also born there. I can’t recall the number but the photo of 18 (previously 12) was at the end of the row of identical houses we lived in. I recall they were connected. There was a row of garages across the street that were for cars. Somebody had a box trailer parked in the open at the end of the row and I accidently locked myself in while playing hide-and-seek once. They backed onto the railway line and the bridge over it. We used to drop stones on the trains as they went by underneath. We occasionally were brave enough to descend to the railway line and put little stones on the line for the train to run over. I was concerned the train would derail from this so didn’t do it often.

My parents ran a sprinkler out the back of the house when it was hot, for us kids to run backwards and forwards through.

There was an Afrikaans family living next door (or maybe a couple of doors over) that we used to play in the mud and sand of their back garden with matchbox cars. I recall their toilet broke for a while and Jannie was very proud to show me how they now took a shit in the bath and then washed it down. I was aghast.

He got measles or chicken pox and I decided to rub my body on his in order to get it too (not sure why). Anyway, it worked and I recall my baths being very prickly affairs for a while as bubbles stuck to the raised bumps on my skin.

My dad worked at AECI as an industrial chemist. He told me years later that one of the foreman/managers asked him to dispose of a couple of pounds of lithium (or potassium or sodium, not sure). He used to take a few small pieces to the beach with us and throw them out the back of the waves. We would watch it bounce around and explode. After a while, his boss asked him how he was progressing. He had hardly made a dent, so the boss said they would concoct a system to get rid of it all on mass. He put it in a metal tin and drilled two holes in the side. He then put this tin into a 44 gallon drum and weighed it down with rocks. A couple of holes were drilled into the side of this big drum. They took this to the slimes dam out the back of the factory one weekend, rowed out to the middle of the dam and dropped the drum overboard before hurriedly rowing back. The idea was that water would enter the big drum, gradually find it’s way into the smaller drum, react with the alkali metal which would create pressure and push the water out of the small drum – to then repeat.

After waiting for a while, my dad reluctantly concluded that it must be working, when the entire slimes dam launched itself into the sky and blew out every window in the rear of the factory. His boss looked him in the eye, said “we were never here” and they both left.

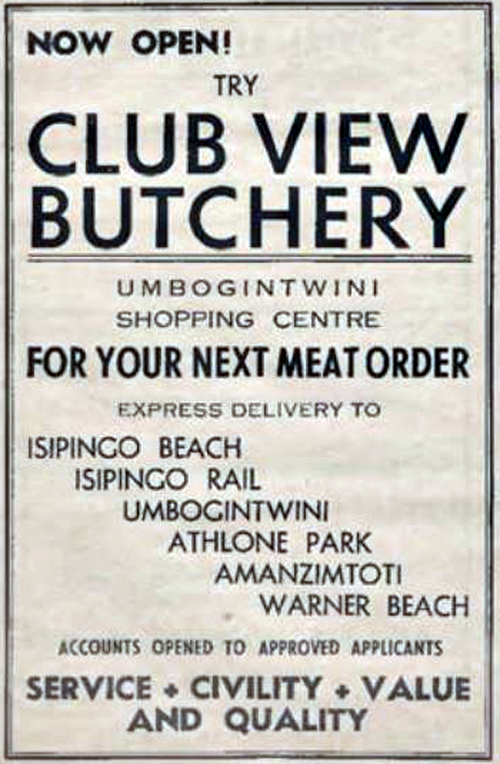

I recall the butcher (and flies in his window). Pretty sure the barber we got taken to was in the same little complex.

My dad took another job at Bostik when I was about 7, so we moved to Port Elizabeth. He stayed with them until his retirement after they bough Genkem. However, my mom was one of a twin and 8 children, so we used to spend holidays in Durban every year, staying with aunty Kathleen and family.

Oh yes, I too live in Brisbane now

This is a long shot as have been trying for many years to find my Mothers family. My mother Yvonne Newton moved to Twini in 1948 with her mother. Her mother married Cecil Muir & he had 3 children. Their names were Treasure, Cecile & Joan. Yvonne was sent back home to the UK in 1951. Unfortunately she was 10 when sent back & had no way of keeping in touch with the Muir’s. She is now 83 & has tried for many many years to locate any of the Muir girls. Any help would be appreciated.

What research plus memories ! So many names ring a bell ! My memories of the surrounding bush are unforgettable. we made hideouts, dongas and tree houses and ate the enormous guavas , which must have been planted by early Indian settlers? Our house was built by my father , with constellations of stars for lights and all the furniture built in . I was sad when driving past ten years ago to see that the house was painted pumpkin and the surrounding verandah was boxed in with aluminium windows. Our mother’s beautiful collection of indigenous plants was no longer to be seen . These plants were collected from sites where our papa built bridges . I remember playing with bramwell girls, Helen , Susan and Francess, the Smillie girls Anne and Margy ( I still see Margy occasionally). And of course Mrs Anderton, and her shrill laugh, such a lover of animals. She used to feed the monkeys with bags of gemsquash and oranges. Once she went on holiday and her domestic helper took the bags home to feed her family. The garden was subsequently wrecked by the monkeys

Ps I also remember being friends with Robby McClaren, from junior school who then went to Epworth . Glynis Olver, with whom I went to Durban Girls High (both of their fathers worked at Kynoch factory). Alan Yates is still a friend . He lives in Glenwood after living in Austria for about 16 years. I met Wendy Maclaren a few years ago at an art exhibition .

Phew Ken talk about the exploding universe. I lived on the corner of Scully Road and John Coke behind Eggy Mathews from 1961 until 1968 until we moved to Athlone Park on the corner of Heather and Chelsea Road just south of the pedestrian Bridge. I am the same age as Clive and knew him from athletics in primary school.

My father was John Swanepoel a large tall person who retired from PERSPEX after working for AECI after 42 years of service, a real feat.

I know many of the names on this page as well as the siblings and often reflect that we had the privilege of growing up in the garden of Eden including the snakes that was Twini village. You forgot the Wise’s cherry hedges.

I still live in SA up here in Benoni and have never thought of immigrating just to annoy the government.

My special teacher at Twini Primary was Mrs Kinnear who decided to keep after school and teach me how to write properly over a number of sessions which to this day often attracts compliments.

Just think all those pretty girls at school are grandmothers, even great grandmothers which must mean I am a grandfather which I am, although my grand daughter lives in Perth.

The rule at Mrs Anderton was that you always had to great her on arrival and say goodbye when leaving.

Ken I remember seeing your birds egg collection, it was impressive, but today you would probably be arrested for not having a license to do that especially where you live now.

I played soccer for Twini Park from when Jimmy Rice started the club right from under 12 all the way to under 16 when I stopped because I played first team rugby at Kingsway.

In closing two years ago I travelled right around Ireland as my wife had inherited citizenship from her grandmother and did a pilgrimage to Arklow specifically to see where the Irish families from Umbogintwini came from.

Hey Mike, thanks for sharing your message…it sparks me to write just a bit…I worked my first years (2/) as an Instruments Mech at AECI and was an active member of the founding group of the Durban Aquirist Society/Club…Iknew your Dad personally as a much respected “Uncle” Swany when he was the big chief at Acrylic Products in AECI …we used to buy the scrapped 10mm glass and make “fish tanks/aquariums”from the scrap (4ft, 5ft, right up to 8ft) tanks and filter systems…I used to arrive with my 1979 Toyota Hilux bakkie and a whole.lot of carpets and blankets to pickup the glass at the end of month…

I believe that some of these aquariums/tanks are still around today, some with the first owners and other times over (talk about recycling) thanks for sharing your post, lotsa love and kind regards, Larry

Wow what a fabulous blast from the past. I have just been totally engrossed by the details and the memories. Names that have popped up that reminded me of so much. Thank you for dedicating so much time to this. I was at Umbogintwini Orinary from 1961 to 1967 then sadly I was sent to DHS. My parents built one of the very first houses at windy corner 733 Kingsway. More houses followed. The NcNaught Davis were a short stroll away through the bush across 2 plots and they were situated between Peace Road and Kingsway. Eventually the Neville’s built a house on first of the vacant plots so thereafter we had to walk along Kingsway to get there. Anne and James Anderton built their house and pool next door to us on the opposite side and eventually built another below windy corner at the end of wave rest road. The Dummets lived directly behind us in Ramble Road. Next door to them lived the Smilies before they moved to another AE&CI either modderfontein or Sasolburg. My father Dirk built a number of bridges some of which were demolished long ago. The pedestrian bridge over the railway line at amanzimtoti comes to mind as it was his very first one. Another one was the previous bridge over the N2 at reunion at the old airport. The last one was the bridge at Dickens Road. My siblings are scattered around. Disa was the eldest and she lives in Holland. Dirk was next and lives in Vancouver. Ingrid lives in Durban. I live in the Western Cape on a farm with the nearest village Stanford and the nearest town Hermanus.

Hi Mark,

Gee what a blast, had to share this will all I knew from ‘Twini.

Don Falconer and my brother Neil moved there circa ’61/61, after my Mum Pam remarried Harry Rowntree, into 7a Oppenheimer Rd, a semi.

Schwegmann’s over the road, Smit’s and Devantier’s tribes on the other corner and Hewitt’s next door, Terry being a great friend.

Tony Roost the then PSHS Drum major up the road.

We had such a great time there in the bush to the river, tree house etc, and the bush trail to UGS via the amphitheatre.

My 2 other siblings were born viz. Mark and Ann Rowntree.

It’s always been a bit confusing in most circles whether Neil and myself were Falconer’s or Rowntree’s. We opted to retain our birth name.

We later relocated to 13 Highbury Rd opposite you.

What great memories I have of all the things we did for ‘Twini. Raising money for ‘Twini Park FC strip and tour, Youth club behind tennis courts to keep us off the streets at night etc.

I went to PSHS where my siblings all attended Kingsway.

I might mention, When Maudy Smith and I used to go surf in town, Addington, Crane, Pumphouse area, we were known as ‘Toti Trash, and them we referred to as Town Clowns.

Oh my goodness. Such memories of a wonderful childhood. Thank you so much Ken, I remember you well. So many memories came tumbling into my memory with all the names of people and places. We moved to Athlone Park around 1958/9 (lived in Ocean View Road, Chelsey Drive and later Kingsway) and I went to Umbogintwini Primary School and the onto Kingsway High School. My life long friends are Penny Sheares and Deanne Tunmer (Deanne has recently passed away). And so many names already mentioned I remember. What a great carefree childhood we all had? Took it for granted and thought it would last forever. So sad to read about all the changes. Married at the Presbyterian Church and had my reception the Jubilee Hall. Myfather worked for Saiccor. I now live in England and retired from nursing, teaching and owning a few businesses. Now in the world of story telling so this is right in my line of interest. Thank you so much.

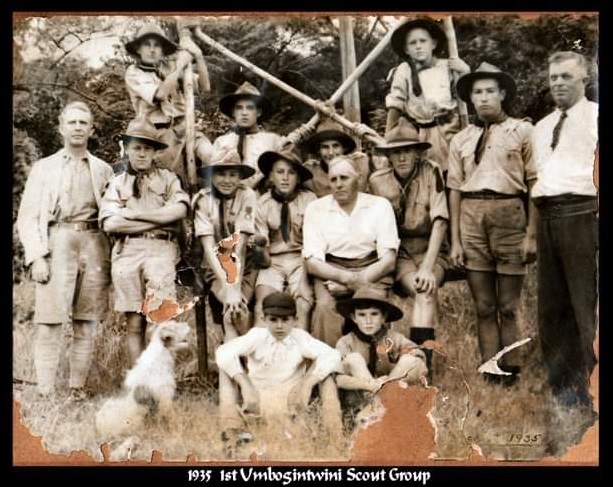

Wow… awesome to find. Thanks so much Ken. My dad was Dave Williams industrial chemist who worked in the lab 1966 – 1982 with a few years in Modderfontein. I was born in 1967 and we lived in 10 Chamberlain Road until I was 5. I was a springbok scout at 1st Umbogintwini in 1984. I remember Wim Hoffland. My mum Wendy (Gwen) Williams was part of the Woman’s Institute. Thanks again. Bill

Robin , its good to know you still around and are sharing our amazing history, soon we may all be gone but our legacy must continue to give hope to those who can only but dream of what we had.

Were do you live now.

When I was young my father used to work for Titan umbongintwini please update me about that Company

Hi, absolutely loved reading your article..my late dad Mr RG de Greef worked at the AECI in 1961 for several years and I was born at the factory hospital in 1962 Brigitta de Greef . Lived 2 years in Umbogintwini Opperheimer St then moved to Amanzimtoti till 1989 where my brothers and i all went to school. Am interested in reading the book on the history om Amanzimtoti …where can i buy this? Tx

Hi I lived next to Eggy in Highbury Rd 1968 to 1974 My name is Mike Cain my closest friend were Gill Emesly Don Roundtree and Mario Chelen. Thank you for the memories and info. We were so lucky to grow up inTwini. All the best to you All

I so exited that someone put pen to paper,( thanks so much Kenny) and wrote about the best place to grow up as a child and teenager. All your exploits about fishing, walking for hours in the bush and on the beach brought back wonderful memories for me. I used to tell my grand kids about the life we shared. Now to hear from others who shared in our youth. Watching the new south coast highway being build was a nice past time every day after school.

Once again we were so very blessed to have been part of the Athlone Park, Twini and Toti experience.

Hey Jimmy! I don’t know if you remember me but here goes anyway – Rob Willis, lived in Umbogintwini, went to Umbogintwini Primary school and then Kingsway High School. Very much remember your mom who was a friend of my mother’s. Great to know you are still around.

What amazing memories. We loved growing up in that village. I was part of the other Kelly Family. My Dad was Leo and my Mom Lyn. There were 6 of us kids that lived in Twini. My older sister Rhonda was married by then. Which left Arthur, Colette, Shevaun, Leo, Maire & Faron. We started out in 12 Highbury Road then moved to 10 Highbury and 9 Highbury Road. Our last address in Twini was 6 Oppenheimer Road opposite Theo’s, next door to the Anglican Church. Growing up with us in Highbury Road we’re the Winnings, van der Westhuizen’s, Bohmer’s, Thorley’s, Heroldt’s, Nortje’s, Scott’s, De Chelin’s, Grubb’s, Rountree’s and Eggy’s family.

We had the best childhood and made lifelong friends in the village.

Hi Shevaun, you may not remember me but l lived with my aunt in 24 Chamberlain Rd. My cousins are Lisa & Eddie Olivier. It was wonderful living there. It is nice to read messages from familiar people you have’nt seen and heard from many years.

Wonderful narrative, thank you Ken. Such wonderful childhood days. I lived in Emoyeni Drive, Amanzimtoti in the 50’s through 70’’s. My Dad, John Walsh, was assistant chief electrical engineer at Kynochs for many years. I went to school at Toti junior school but then high school at Marist Brothers in Durban after a stint of boarding school in Kloof. My brother Howard went to Kingsway High. My sister Sue was at a convent in Malvern. I did arts and law at Howard College, then after articles of clerkship in Durban I worked in East London and later Johannesburg as an attorney before settling in Australia. I now live on the Queensland Gold Coast at Mt Tamborine. One of many scatterlings of Africa, I treasure memories of Twini and Toti. Thanks so much for your wonderful history of those early days. Alan Walsh

This was such a surprise to have come across. I’m part of a much younger generation that lived in twini. I went to Umbogintwini Primary School and then Kingsway High. Which I then started nursing training at Kingsway Hospital. From 1991 until 2000 we lived in 23 Highbury Rd. I possibly had the best upbringing living in the village. Us kids would be out on the streets from the moment our eyes were open until midnight for most of the school holidays or wknds. We were known as the village kids but I would not trade that nickname for anything in the world. And the amazing thing is, all us kids then are still in contact. The club pool was a huge hit for us and I remember doing karate at the “Club hall”. The army camp was also a highlight for us on highbury Rd, as well as the park which we spent hours at. Challenging each other to see who could ride their skateboard or Rollerblade all the way from the top of John Coke road to the bottom without wiping out was always a fun time as well, hoping our back fences to get to friends houses. It is such a pity that such a beautiful village was destroyed. Thank you for bringing back this memory for all of us to relive again.

Great read – well done – I have fond memories of living at 35 Highbury Road opposite the little church. Amazing changes have taken place since then !

Gordon Blackwood – now living in Scotland

I’m most impressed with the detail of my old stomping ground, having grown up in Athlone Park but so very often venturing across the main highway through the bush path and down the ash road to Twini Station to catch a train to Durban. It’s a remarkable piece of writing which brings back so many memories. Thanks a ton to the author who I recall in name as well as the other individuals mentioned. The mention of Durban City and Durban United were significant as I spent many years writing Soccer Through The Years 1862-2002. Well done to Ken for keeping the area’s rich history intact for generations to come.

I sit here in Perth Australia but as I read this my mind is in Umbogintwini in the 1980’s. Thank you so much Ken for the wonderful trip down memory lane. My Dad (Errol Hulley) worked at AECI and we lived in Chamberlain Road before moving to Shepstone Road where I spent most of my childhood. Memories of riding around Twini on my bike getting up to all sorts of adventures have come flooding back. I have often tried to find old images of Umbogintwini without much success, so this has made my day!

Ken, thank you for the many hours of work you have put in here, brings back so many memories. I’m so sad to hear about the loss of Jenny, we were both good friends but circumstance and time pulls people apart, she had good heart. We lived in 23 Chamberlain Rd, next to the Inngs’ home before the new FM’s house was built before moving to Windy Corner and Toti.

Hi Ken,

It was a delight for me reading your history of Umbogintwini. I wrote an account of our family’s time in the village from 1942 to 1947 as a nostalgic need, remembering happy times in my youth. I am re-writing it and making additions from what I have since remembered, triggered and inspired by your article. This so that my children and grandchildren may possess some history to reflect on in addition to other writings I have done on their forebears.

I was younger than you were and not as aware, to the degree that you were, of many things in your story. I shall, of course stick to my memories and cannot, unfortunately, add anything of significance or any photographs to your story. I was very pleased to have, from your writings confirmation of what I remembered and a most interesting wider knowledge of the village, and geological and other history.

Ken, thankyou for this blog-brought back many memories. Actually lived in Athlone Park then and did Std. 4&5 at Twini school in 68/69.I recall knowing Jenny when I went onto Kingsway High… not in same class but in same standard. Sorry to hear of her passing.

Some names crop up in your blog.. Vim and Corine were our neighbours. I am again only now in contact with Wim again after all these years… thanks to fb!

Allan Druce used to play at our methodist church in Athlone Park..great musician.

Once i got my drivers licence, i used to shoot down daily to the twini station in our beetle to collect my dad arriving from working in durban.

Thanks again

Hi Ken and other twini-ites,

Thanks for all the memories. Yes we had it good to say the least.

Other memories were teacher Miss Tandie who was passionate about SA history especially the battles of Rourkes drift, Isandluwana etc. Miss Pascoe was my favorite.

Glynn Crossley (Hawk) the scout master. Go cart races down John Coke hill. John had the best cart. Movies at Jubilee hall. Especially Game capture in Rhodesia when Kariba was filling. The “session’s” and Discos. Guy fawkes at the club and at “yokkies” house. Swimming at Mrs Andersons pool on Ocean way. Bicycles, skate boards, surfing, fishing, birding, camping on Sandy bank. Derek, Malcolm, Richard, Robin, Cederic, Jimmy, Niomi, Ken, Martin, Ann, John, Marlene, Karin. Mrs mac Naught Davis. Steven, Judy, and many others. I also served time at the Bottle store.

Photos would be appreciated.

Currently living in East London area.

Hey Len

So good to see your message. So well remember the times we all shared in Chamberlain Road, at the scout hut, on Sandy Bank and at school. Many memories came flooding back reading your account. I think I remember that you had a little dog called Bandy – am I right? We had many good times together with the other guys you mention in your post. I presently live in the Netherlands with my wife and kids and grandkids.

…many many others!

What a wonderful environment to be brought up in – no high walls, electric fences or security gates. Our only security was the patrol men with knob kerries which you mentioned – and the 10 o’clock curfew siren from the factory. Many of the names were after my time but the places brought back awesome memories of long ago. We stayed at No 20 McGowan Road and both my parents were very involved in the dramatic society which held amateur productions at the Jubilee hall from time to time. Great memories – thank you.

In 1964 Pop Fearon persuaded me to try the High Jump event. From then on to Matric, Kenny Grubb, Robin and I competed. Kenny always first with me getting 3rd or 4th positions. Kenny’s best – was it 5 foot 11 and a half? Or his own height?

Jumping scissors into a sawdust pit! Teaching Fosbury to my jumpers at school over the years somehow came easily. The first 15 or so years, I was able to impress my pupils by jumping scissors onto the mat, at heights some could not achieve.

Lots of memories brought up here. Thanks Kenny! Memories in your back yard and the tamed wild birds under your care. That crow of yours!!

Can’t remember who all was there when two Peters, Ian and ? were returning from nesting and exploring Isipingo Flats side, We had to cross the Twini river. The others were ahead of me when I sank past my knees in quicksand. Desperate screams brought my rescuers back. That was scary!

Having taught in East London for 26 years, I missed all the hype about Twini Village being obliterated. St Johns, Jubilee Hall(remember the sessions there) Mrs Marisch’s Bottle store ( I also worked there. Remember having to enter every single purchase in the register, under spirits, fortified and unfort.ified wines! ) Theos and the village. All gone! I believe there is a lot of controversy over the condition / fate of the Catholic Church. This country of ours is so far behind the world in historical places. The systematic neglect and destruction of our”baby” history depresses me no end.

I have been retired and living in Assagay/Hillcrest for the past 8 years. House is on the market and heading to join my daughter and granddaughter in England,

Military training at 1SSB in Bloem and teacher training followed by 9 years teaching in Ixopo then East London for 26 years, separated me from friends and home. This I regret so much, and so reading your story brought back so many memories. Thanks for that.

Reminder. I was Roderick Saunders up until about Std 8, when I chose to have my birth name. Cherryll Barry and Shirley my siblings. 8 Hudd Rd Then 21 Marshall Rd

Thank you Ken for wonderful memories of a great place to grow up in. We lived in Blewett road then moved to Highbury Road opposite the Jubilee hall. Have wonderful memories of happy times and great friends from twini . Started school at twini in 1957. Before moving to Toti primary. Then Old Kingsway High. Got married at the Athlone Park Presbyterian church in 1970. Now living in Australia. In the same road as Tony van der Westuizen. We lived opposite in twini village. How’s that for coincidence. Thanks for the memories. Much appreciated

Hi Ken

Thank you for taking me on a journey about my childhood.

I must have been in your class at Twini Primary and then in Std6 at Kingsway.

We lived at 21 Oppenheimer Road. My dad Bill Bell was Instrument Engineer for many years,

Wow, what great memories. I lived on a small holding in Old Main Rd Toti in my early years but went to Twini primary. Later we lived in Wave Crest Rd and then Dawn Place before getting married and moving to Warner Beach. moved to Australia in 1983.

Had lots of friends in Twini Village so spent some special times there.

Thanks so much for sharing these memories.

Kind regards

Denzil

Thank you Ken for such an informative read on Twini. Although I was a Warners girl, we ended up at 616 Kingsway for my High school years and have very fond memories of the Twini that was. Thank you for sharing this wonderful article!

A great read – which I plan to reread! Thank you for documenting our fortunate lives, growing up in Twini, Kenneth! Wonderful memories! I went to Twini school with you! My Dad, Allan Druce was the Assistant Chief Chemist at AECI all his working life – and was also very active in the music scene – teaching and playing the piano and organ -at most of the churches – and even for “Cocktail Hour” at the Twini Club! I now live in Qld, (near where I believe Mark is!)

Hi Karen

It was so good to see your comment.

I remember you and your Dad so well. He played at our wedding at the St John’s Anglican.

I was very good friends with Lesley.

Lived in Chamberlain Rd in 1975 and attended Umbogintwini primary school. Wonderful memories.

Thanks for bringing back some wonderful memories of Twini village,I worked at AE&CI for 23 yrs and lived at a few addresses in Twini Village.

What a fantastic read, it brought back wonderful memories of my early years in the area. I lived in Prince Street and my sister Helen and I went to Twini School after arriving from England in 1967. Friends for life were made at Twini Primary, Kingsway Junior High and Kingsway Senior High. Thank you so much for writing this Ken.

Thank you for this it brought back so many memories. My parents and myself when I got married lived in the Village. I remember the Kynoch Xmas parades and sports days as well as the Nativity plays.

I will see if I have some photos from my parents

Wow, great memories!

We didn’t realise then, how good we had it!

Thank you for a very interesting read…

My mom and Dad, Jimmy Acker and Pauline Acker lived at 16 Chamberlain then 18 Chamberlain Rd for many years. (1970 to 1983 ish) I recall ken Grubb? Or was it Ben…We had a wonderful child hood in Twini, from my sister doing Pottery at the Hall in the grounds around Jubilee Hall, to playing around the village…wonderful memories.

We lived in number 18 until it was demolished, such great memories in that house

Hi Ken, my name is Joy Herbst (nee Whiteley). It was wonderful to read all the history of our lives living in Twini. It really was a special place. Jean (76) , our eldest sister, lives in Auckland with her family; Jennifer (72), lives in Hillcrest & is about to remarry on Saturday 16th April after her beloved first husband passed away 3 years ago from cancer; Laura Jayne (62) who was born in the Kynoch Hospital & delivered by Dr McCleod when we lived in McGowan Road is living in ‘Toti and myself (74). I live in Knysna. My Dad Jimmy sadly died when he was 57 and had been boarded from Kynoch perspex division due to a bad heart. My mother Joan died at 84 years in ‘Toti in 2011. She never left the area.

I have many wonderful memories of the milkman who parked his cart at the Jubilee Hall. The Frangipani tree outside our house at 19 Highbury Road where my sister Jean hung upside down most afternoons. Bert Burness bunking school brought back wonderful memories. Felicity Sangster was my best friend up the road Kevin & Cheryl Cole lived over the road. The many Variety Concerts at the Jubilee Hall which our family were a part of. And. And. Thanks for bringing it all back, some of which I had forgotten. Joy

Loved reading all the details in your writing. I too have wonderful memories of our time in Athlone Park and going to the Beach and walking under the railway bridge onto the Red Sandune across the highway pre 1974.

Running to the Beach when the plane crashed with My Brother Mark Daniels. He was friends with your Brother. The scout Hall where I attended Guides. Not to forget the weddings at Jubilee Hall and Tennis Lessons. The post Office Next to the Huge tree. Garage and Shops.

Such Special times at the beach with our family.

So many of the famous names you have mentioned also bring wonderful memories back too.